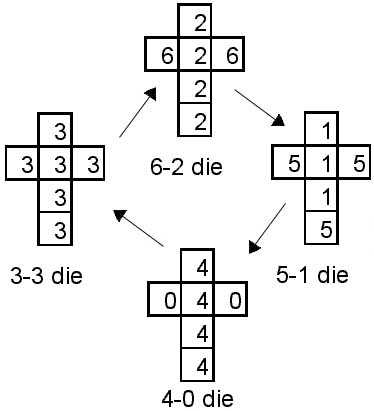

Chaque dé représenté ci-dessus a deux fois plus de chances de gagner que le dé proche et désigné par une flèche : le dé qui comporte des 4 l'emporte sur le dé des 3 qui l'emporte sur le dé des 2 qui l'emporte sur le dé des 1. Mais, curieusement, ce dernier (avec des 1) l'emporte sur le dé qui comporte des 4 ! La relation deux à deux de ces 4 dés est intransitive. La démonstration se trouve dans les 6 tableaux juxtaposés ci-dessous. Chaque tableau étudie une paire de dés : le premier y figure verticalement et le second, horizontalement.

| 12 3 3 3 3 3 3 | 12 2 2 2 2 6 6 | 12 1 1 1 5 5 5 | 12 4 4 4 4 0 0 | 18 3 3 3 3 3 3 | 16 4 4 4 4 0 0 | |24 36 |24 36 |24 36 |24 36 |18 36 |20 36 | | 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 | 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 | 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 | | 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 | 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 | 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 | | 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 | 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 | 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 | | 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 | | 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 | | 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 | 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 | 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 |

Dans le premier tableau, les faces du premier dé (444400) sont dans la première colonne. Celles du second dé (333333) sont en première ligne. Dans le tableau croisé 1 signifie que le premier dé l'emporte sur le second. Dans ce premier tableau, on voit que le dé (444400) a 24 chances sur 36 de l'emporter sur le dé (333333) car il y a 24 fois 1 dans le tableau. En effet, les faces 4 l'emportent sur les faces 3.

Dans le second tableau, ce même dé (333333) a 24 chances sur 36 de l'emporter sur le dé (222266) car les 3 l'emportent sur les 2, mais pas sur les 6. Le tableau suivant montre que ce dé (222266) a aussi 24 chances sur 36 de l'emporter sur le dé (111555). Curieusement, le 4ème tableau démontre que ce dernier dé (111555) a 24 chance sur 36 de l'emporter sur le tout premier dé (444400). La supériorité de ces 4 dés l'un par rapport à l'autre ne constitue donc pas une relation transitive.

Quand est-il des 2 autres paires? Les dés (111555) et (333333) ont la même probabilité de gagner l'un sur l'autre (18 chances sur 36) et l'affrontement des dés (222266) et (444400) serait presque aussi incertain (l'un a 20 chances sur 36 et l'autre 16).

Si vous laissez votre adversaire choisir son dé, vous pouvez choisir un des 3 restants : statistiquement, l'un gagne, un autre perd et le gain du troisième est incertain (exactement ou presque). Si vous imposez de jouer au moins une dizaine de fois, vous pouvez donc à votre guise choisir le dé du gain, le dé de la perte ou celui de l'incertitude. Bref, votre adversaire est entre vos mains et l'usage de ces dés constitue tout simplement un abus de son ignorance.

Disponible ici: http://www.grand-illusions.com/acatalog/Non_Transitive_Dice_-_Set_1.html#a33

Voici une article plus détaillé tiré de la

revue "Science News"

Week

of April 20, 2002; Vol. 161, No. 16 , p. 0

Tricky Dice Revisited (by Ivars Peterson)

The game involves a set of four cubic dice, each one numbered differently. You let your opponent pick any one of the four dice. You choose one of the remaining three. Each player tosses his or her die, and the higher number wins. Amazingly, in a game involving 10 or more turns, you will nearly always have more wins.

After the first session, you can invite your opponent to pick a different die, perhaps even the one that worked so well for you. You select one of the remaining dice. Again, in a game of at least 10 throws, you're very likely to come out the winner.

Indeed, it doesn't matter which die your opponent picks. You can always choose another die that will practically guarantee your triumph in a game of 10 or more turns. For this particular set of dice (right), the die with four 4s beats the die with six 3s, which in turn beats the die with four 2s, which beats the die with three 1s, which (completing the cycle) beats the die with four 4s! So, it doesn't matter which die your opponent picks. You can always choose another die that practically guarantees your triumph in a game of 10 or more turns.

Dice numbered in this fashion are known as nontransitive dice. They were designed by statistician Bradley Efron of Stanford University to help illuminate probability paradoxes that involve the violation of a mathematical property called transitivity. In the case of the four dice shown above, the surprise arises from the mistaken assumption that the relation "most likely to win" is transitive between pairs of dice. It is not. The first die in the sequence is twice as likely to beat the second die, the second die is twice as likely to beat the third die, the third die is twice as likely to beat the fourth die, and the fourth die is twice as likely to beat the first die.

Efron came up with two additional sets of four dice that show the

same nontransitive property.

SET 2: (2, 3, 3, 9, 10, 11); (0, 1,

7, 8, 8, 8); (5, 5, 6, 6, 6, 6) and (4, 4, 4, 4, 12, 12).

SET 3:

(1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11); (0, 1, 7, 8, 8, 9); (5, 5, 6, 6, 7, 7) and (3,

4, 4, 5, 11, 12).

A set of three dice can also have the same nontransitive property. SET 4: (3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 7); (2, 2, 4, 4, 9, 9) and (1, 1, 6, 6, 8, 8).

In set 4, the first die beats the second, which beats the third, which beats the first. As it happens, this set uses all the numbers from 1 to 9. Moreover, the numbers can be written as a magic square, in which the rows, columns, and diagonals each add up to 15.

8 1 6

3 5 7

4 9 2

In the example above, each row gives the numbers for one die.

Hence, the three dice all have the same total face value (30). Other

magic squares also yield nontransitive dice sets. Here's another

example of three nontransitive dice, where all the dice have the same

total face value (42).

SET 5: (1, 1, 1, 13, 13, 13); (0, 3, 3, 12,

12, 12) and (2, 2, 2, 11, 11, 14).

Discovered by Allen J. Schwenk of Western Michigan University, this particular set of nontransitive dice displays an intriguing quirk when the game is changed a little. Suppose you select first, and your opponent picks second. Just for fun, the players also opt to roll each die twice, taking the total. The higher total wins. It turns out that you would still have a winning edge, albeit a small one, even when your opponent chooses the die that would have won under the original rules.

When toy collector and consultant Tim Rowett looked for a commercial product based on nontransitive dice, he initially turned to the first set of four dice, partly because no number is greater than 6 (the highest number on a standard cubic die). Its disadvantage is that one die is all 3s. It's not a very exciting choice for any player. You know exactly what's going to happen with every throw.

Rowett now has a set of three nontransitive dice, where no face

has a number higher than 6, and each die has two different numbers

(adding a bit of suspense to the game).

SET 6: (1, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4);

(3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 6) and (2, 2, 2, 5, 5, 5).

In this case, the first

die beats the second in 25 out of 36 possibilities, the second beats

the third in 21 out of 36 chances, and the third beats the first in

21 out of 36 tries. As with set 5, changing the game so that your

opponent picks first and both of you toss twice (or use a single

throw of two identical dice), again gives you the edge.

What would happen with three rolls? r rolls? These and other variants of nontransitive dice games offer all sorts of possibilities for mathematical exploration (and for trapping the unwary).

References:

Gardner, M. 2001. Nontransitive dice and other paradoxes. In The Colossal Book of Mathematics: Classic Puzzles, Paradoxes, and Problems. New York: W.W. Norton.

Honsberger, R. 1979. Some surprises in probability. In Mathematical Plums, R. Honsberger, ed. Washington, D.C.: Mathematical Association of America.

Peterson, I. 1997. Mailbox: Magic dice, Monopoly, and contra dancing. Science News Online (Dec. 20). Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/sn_arc97/12_20_97/mathland.htm.

______. 1997. Tricky dice. Science News Online (Oct. 4). Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/sn_arc97/10_4_97/mathland.htm.

Rump, C.M. 2001. Strategies for rolling the Efron dice. Mathematics Magazine 74(June):212-216.

Savage Jr., R.P. 1994. The paradox of nontransitive dice. American Mathematical Monthly 101(May):429-436.

Schwenk, A.J. 2000. Beware of geeks bearing gifts. Math Horizons 7(April 2000):10-13.

Toy collector and consultant Tim Rowett introduced his new set of nontransitive dice at the Gathering for Gardner V (see http://www.g4g4.com/). For additional information about Rowett and his toy and novelty collection, go to http://www.grand-illusions.com/tim/tim.htm.

A collection of Ivars Peterson's early MathTrek articles, updated

and illustrated, is now available as the MAA book Mathematical Treks:

From Surreal Numbers to Magic Circles.

See

http://www.maa.org/pubs/books/mtr.html.